The trans-Atlantic mass exodus was a major event in Swedish history, says DAG BLANCK, and the immense network of contacts that was established across the Atlantic has proved important for the way in which Swedish society both then and now has been oriented towards the United States…

Dag Blanck

Immigration to the United States in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was part of an economic and social transformation, when between 1850 and 1950 some fifty million Europeans settled in non-European areas. The mass exodus of some 1.3 million Swedes to the United States during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was due primarily to worsening economic and social circumstances in Sweden. ‘Push and pull’ factors on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as the establishment of migration links, are other important factors that more precisely determined the scope and course of migration patterns. A strong population growth in Sweden increased pressure on a society that was fundamentally agricultural in nature, and moving to North America provided emigrants with economic opportunities not available in their homeland. Religious and political circumstances played a much smaller role, though it was decisive in some instances.

Statistics

Swedish mass-immigration began in earnest during the mid-1840s, when a number of pioneers, often moving as groups, established a migration tradition between areas in Sweden and particular locales in the United States. Examples of colonies founded by these groups include settlements in western Illinois, Iowa, central Texas, southern Minnesota and western Wisconsin.

When the American Civil War broke out, ending the pioneer period of Swedish immigration, the federal Census recorded some 18,000 Swedish-born persons in the United States. Ten years later, following the first heavy peaks of Swedish immigration between 1868-69, largely due to crop failures in Sweden, the figure was almost five times higher: 97,332. By 1890 approximately 478,000 Swedes lived in the United States. During the 1880s alone, some 330,000 persons left Sweden for the United States, the peak year being 1887 with over 46,000 registered emigrants.

The pace of immigration remained high after 1890 and by 1910, the American census recorded over 665,000 Swedish-born persons in the United States. Just as the Civil War had restricted the number of foreigners who could enter the United States, the First World War curtailed the number of immigrants during the 1910s, and by 1920 the number of Swedish-born in the United States declined for the first time, the total population standing at 625,000. 1923, when over 26,000 Swedes left for the United States, represents the end of some eight decades of sustained mass migration.

As the decades of Swedish emigration progressed, a second generation of Swedish Americans began. This second generation was first recorded by the Census of 1890, when some 250,000 persons in the Unites States were classified as second-generation Swedish Americans. During the following decades, this figured increased quickly and by 1910 the second generation had surpassed the first, totalling 700,000. In 1920, the figure was 824,000.

The rural and agricultural profile of Swedish immigration of the first decades gradually changed. By the turn of the century the majority of Swedish Americans were city-dwellers, and a part of the rapidly growing American industrial economy. This reflected a development from the migration of families during the first decades of emigration to a movement dominated by single young men and women after the turn of the century.

Return migration formed part of the pattern. Approximately one fifth of immigrants returned to their homeland. Re-migration was especially strong towards the end of the emigration era, and was more common among men, urbanites, and persons active in the American industrial sector.

Settlements

As the result of immigration, Swedish extraction was well over one million during the first decades of the twentieth century. However, it was not evenly distributed throughout the country. The early phase of Swedish immigration established the Midwestern states as a prime receiving area. The agricultural areas in western Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and western Wisconsin formed the nucleus of the first Swedish settlements. Migration chains were quickly established between many places in the Midwest and in Sweden, encouraging and sustaining further movement across the Atlantic. After the Civil War, the Swedish settlements spread further west to Kansas and Nebraska, and in 1870 almost 75 percent of Swedish immigrants were situated in Illinois, Minnesota, Kansas, Wisconsin and Nebraska.

By 1910 the position of the Midwest as a place of residence for Swedish immigrants was still strong, but had weakened. 54 per cent of immigrants now lived in these states, with Minnesota and Illinois dominating. 15 per cent lived in the East, where the immigrants were drawn to industrial areas in New York City and Worcester, Massachusetts. A sizeable Swedish American community had also been established on the West Coast, and in 1910 almost 10 per cent of Swedish Americans lived in the states of Washington and California. In Washington, a heavy concentration of Swedish Americans grew up in the Seattle-Tacoma area.

Minnesota became the most Swedish of states, with Swedish Americans constituting more than 12 per cent of Minnesota’s population in 1910. In some areas, such as the Chisago and Isanti counties, north and northwest of Minneapolis, Swedish Americans made up close to 70 per cent of the population. But if Minnesota became the most Swedish state in the Union, the city of Chicago was the Swedish American capital. In 1910 more than 100,000 Swedish Americans resided in Chicago, which meant that about 10 per cent of all Swedish Americans lived there. At the turn of the century, Chicago was also the second largest Swedish city in the world; only Stockholm had more Swedish inhabitants.

Communities

‘Svenskamerika’ or Swedish America, as the Swedish American community began to be called around 1900, was a collective description of the cultural and religious traditions that the Swedish immigrants brought to their new homeland. These traditions were both preserved and changed through interaction with American society, and formed the basis for a sense of ‘Swedishness’ that developed among immigrants and their descendants.

Swedish America was split culturally, religiously, and socially, and by the beginning of the twentieth century different Swedish American institutions such as clubs and churches formed an intricate pattern that spanned the entire American continent. The largest organizations were the various religious denominations founded by Swedish immigrants in the United States. These churches had their roots in both the religious experience of the homeland and the United States. The Lutheran Augustana Synod was founded by ministers from the Church of Sweden, the Mission Covenant had its Swedish parallel in Svenska Missionsförbundet, and the Evangelical Free Church developed from the Covenant Church. Other “American” denominations also attracted Swedish immigrants as members. In some cases, as with the Baptists, Methodists, Adventists, and the Salvation Army, separate Swedish-language conferences were organized as part of the American mother institution, whereas still others, such as the Congregationalists, Mormons, and Presbyterians, organised Swedish-language services in the American congregations with some regularity.

The Lutheran Augustana Synod was by far the single largest Swedish American organisation and larger Swedish American denominations did not only serve the religious needs of their members, they also founded educational and benevolent institutions such as colleges, academies, hospitals, orphanages and care homes. Swedish American institutions of higher education became particularly important, and today a group of American colleges and universities can trace their origins to Swedish immigrants, including Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois; Bethany College in Lindsborg, Kansas; Bethel College in St. Paul, Minnesota; California Lutheran University in Thousand Oaks, California; Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota, and North Park University in Chicago, Illinois.

Secular organisations attracted fewer members. Included here are the mutual-aid societies, which included the Vasa Order, the Svithiod Order, the Viking Order, and the Scandinavian Fraternity of America. There were numerous other, much smaller organisations scattered around Swedish America, with various purposes, inluding organisations for individuals from a particular province in Sweden or those focused on musical, theatrical, educational, or political activities. A small, but very vocal, Swedish American labour movement also developed, mainly in the urban areas. At the close of the 1920s it has been estimated that the total membership of these secular organisations stood at 115,000 or just under ten per cent of first and second generation Swedish immigrants.

The different organisations catered to varied needs’ However, they transcended these specific functions and all became places where one could meet fellow country-persons, speak the Swedish language and participate in the various social activities.

Culture

A cultural life quickly developed within the Swedish American community. Much of it was centered on the Swedish language, which was seen as a key factor in both the culture’s creation and maintenance. The Swedish-language press played an important role in this respect, and it has been estimated that between six hundred and a thousand Swedish language newspapers were published in the United States. Some important titles include Hemlandet, Svenska amerikanen, Svenska amerikanska posta, Nordsjernan, and Svea. The Swedish American press was the second largest foreign-language press in the United States, with a total circulation over 650,000 copies in 1910.

Swedish immigrants and their descendants did not only read newspapers. Numerous books, journals, pamphlets, and other types of publications were brought out in Swedish America by a variety of publishers. Book shops sold books imported directly from Sweden so a great variety of books in Swedish were available across the United States, on such subjects as religion, education, history, geography, music and drama. A strong group of Swedish American authors emerged including, most famously, Jakob Bonggren, Johan Enander, G.N. Malm, and Anna Olsson.

Music and drama were an important part of life in the communities. Theatere productions ranged from performances of Swedish elite drama in Chicago to the vaudeville or bondkomik productions of Olle i Skratthul’s traveling troupe. There was even a Swedish American opera, Fritiof and Ingeborg by C.F. Hanson, performed in 1898 and 1900 in Worcester, Massachsetts and in Chicago. Numerous choirs and choruses also existed in Swedish America, many of them joined by the American Union of Swedish Singers.

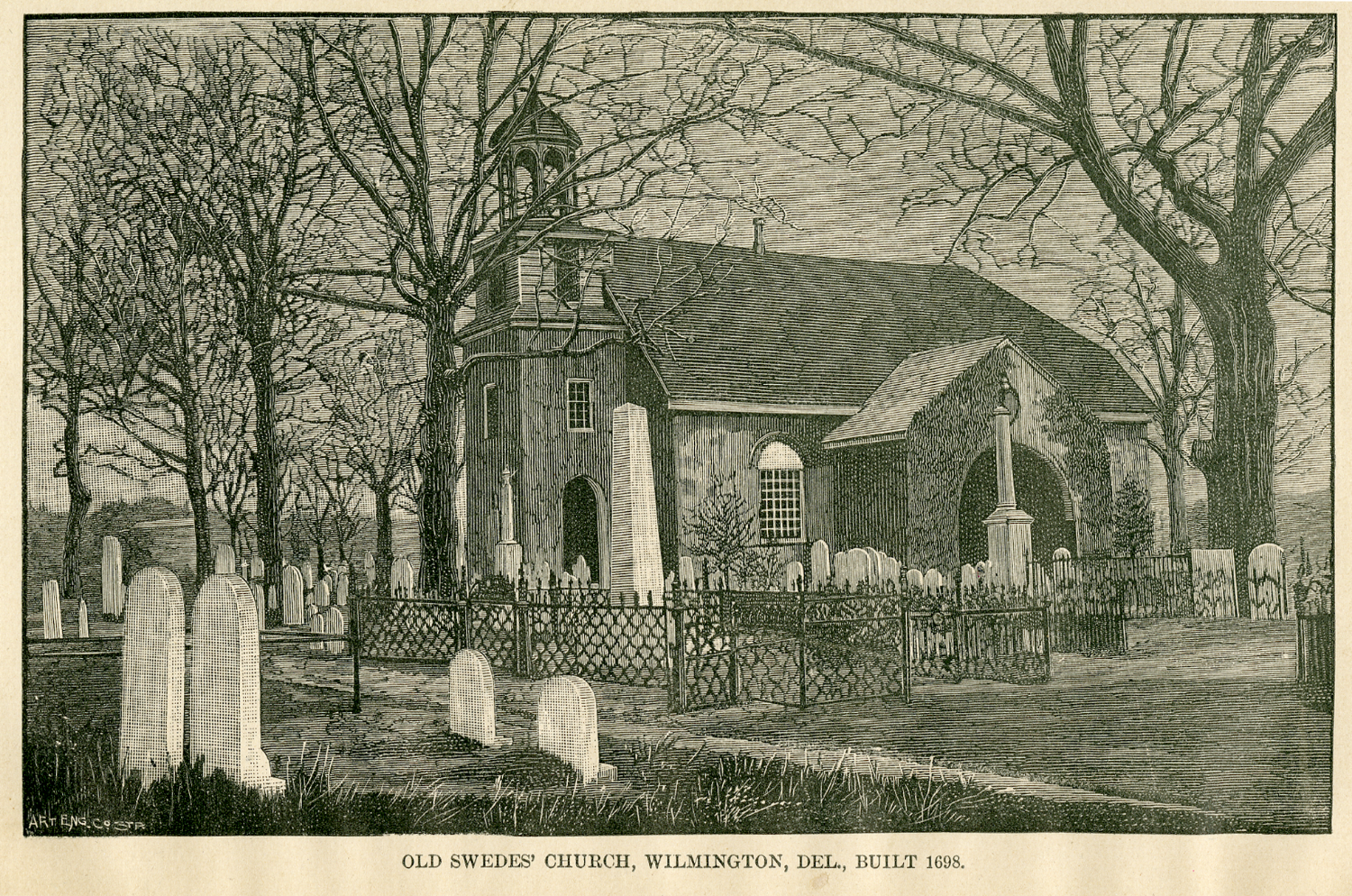

Midsummer celebrations occurred as early as the 1870s and had become quite common by 1900, often filling the function of a Swedish or Swedish American national day. Svenskarnas Dag in Minneapolis has been celebrated in the middle of June since 1934. The 1891 unveiling of a statue of eighteenth century Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in Chicago provided that city’s Swedish Americans with many opportunities using the monument as a Swedish American rallying point. Swedish Americans have also used Fourth of July parades to mark their dual loyalties to both the United States and Sweden, and have commemorated their own history several times at both the 100th and 150th anniversaries of the beginnings of Swedish mass immigration to the United States in the 1840s, and by celebrating the 250th, 300th, and 350th anniversaries of the 1638 establishment of the New Sweden Colony on the Delaware River.

Today

Four million people responded ‘Swedish’ to a question of ancestry in the 2000 U.S. Census. Swedish America today consists overwhelmingly of descendants of Swedish immigrants, many of whom are by now in the third generation or later. The number of immigrants from Sweden in 2000 stood at some 50,000. Hundreds of Swedish American organisations still exist, including museums in Philadelphia, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Seattle and the Swedish Council of America functions as an umbrella group for Swedish American organisations.

Expressions of Swedishness are visible on many holidays and Swedish Americans often show an interest in traveling to Sweden. The Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois is a national archive, library, and research institute for the study of Swedish immigration to North America and provides a wealth of information for those who wish to pursue research in the field, publishing the Swedish American Genealogist, the only journal in the field of Swedish American genealogy. The Swedish American Historical Society is also devoted to the study of Swedish American history, and publishes the only journal in the field, the Swedish American Historical Quarterly.

DAG BLANCK is a professor of North American Studies at the University of Uppsala, and is the director of their Swedish Institute for North American Affairs. View the original article here.

This article has also been published by the Minnesota Historical Society. It has been republished with their permission.